Recognizing Highly Sensitive Person Traits in Clinical Practice: What Every Clinician Should Know

An Introduction to Highly Sensitive Person Traits

In 1997, Elaine N. Aron, PhD released her groundbreaking research on the term “Highly Sensitive Person” or HSP, creating an ever-evolving framework under which clinicians identify, understand, and support clients with Highly Sensitive Person traits. Today, clinical studies suggest that nearly 20% of the population present with highly sensitive person characteristics [1]. For the purpose of gauging highly sensitive person traits, it is also important to see sensitivity as a spectrum rather than one extreme or another. While 20% of the population may show signs of being highly sensitive, roughly 50% of individuals may present with a moderate degree of sensitivity, and 30% may present with relatively low sensitivity [2].

A Highly Sensitive Person is a neurodivergent individual who is thought to have an increased or deeper central nervous system sensitivity to physical, emotional, or social stimuli [3]. HSP traits are innate and the brains of highly sensitive persons work a little differently than others.

Defining Highly Sensitive Person Characteristics

There’s more to being an HSP than just being sensitive to stimuli. Other Highly Sensitive Person characteristics include:

- Deeper processing of environmental stimuli

- High levels of emotional reactivity

- Heightened physiological reactivity to behavioral inhibition

- Stronger unconscious nervous system activity in stressful situations

- Experiencing strong negative and positive emotional responses

- High levels of perception for subtle differences

- Low tolerance to high levels of sensory input

- Experiencing a low pain threshold [4]

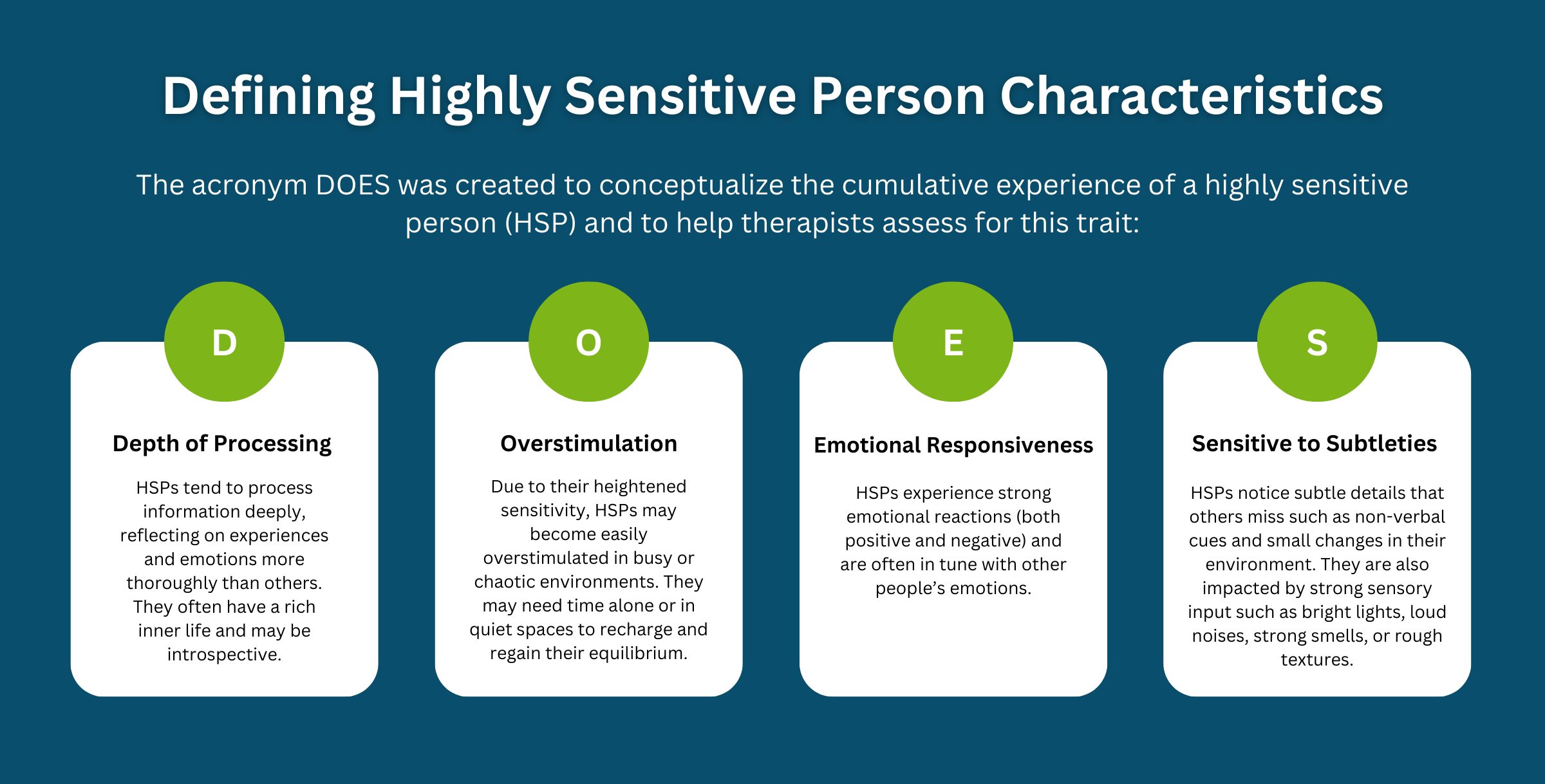

In her book Psychotherapy and the Highly Sensitive Person, written to help therapists better understand HSPs, Dr. Aron created the acronym DOES to conceptualize the cumulative experience of a highly sensitive person (HSP) and to help therapists assess for this trait: [5]

- Depth of Processing – HSPs tend to process information deeply, reflecting on experiences and emotions more thoroughly than others. They often have a rich inner life and may be introspective.

- Overstimulation – Due to their heightened sensitivity, HSPs may become easily overstimulated in busy or chaotic environments. They may need time alone or in quiet spaces to recharge and regain their equilibrium.

- Emotional Responsiveness/Empathy- HSPs experience strong emotional reactions (both positive and negative) and are often in tune with other people’s emotions.

- Sensitive to Subtleties – HSPs notice subtle details that others miss such as non-verbal cues and small changes in their environment. They are also impacted by strong sensory input such as bright lights, loud noises, strong smells, or rough textures.

These characteristics, when experienced individually may cause minor inconvenience to a person’s daily life, but they have a greater impact on highly sensitive persons and may co-occur alongside anxiety and depression. They can also result in physiological symptoms like headaches and feeling cold.

FREE DOWNLOAD: This handout is designed to help your clients with highly sensitive person traits thrive in everyday life.

Recognizing Highly Sensitive Person Traits in Clinical Practice

The presence of HSP as a personality trait requires a nuanced approach within the clinical setting. Clinicians must perform a formal assessment complete with a full exploration of the individual’s personal history, behavioral observation, and measurement tools in order to capture a complete picture of each client.

Highly Sensitive Person Scale

One measurement tool, created by Dr. Aron, is a highly sensitive person scale for individuals curious about whether they have highly sensitive person traits [6]. There are two variations to this HSP scale; one for adults, and one for children. The self-assessment consists of 14 statements and is scored by how many statements reflect an individual’s experience; the higher the score, the more likely an individual is to be categorized as a Highly Sensitive Person.

Lived Experience as a Highly Sensitive Person: Nōn’s Story

Content Warning: Mentions of depression, suicide, alcohol, eating disorder, self-harm and a brief mention of animal abuse.

Content Disclaimer: This is a first-person account of someone with lived experience. It is not the story of a medical professional, nor does it qualify as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

I was 16 years old when clinical research psychologist Elaine N. Aron, PhD first introduced the world to the term “highly sensitive person,” in her book1 of the same name. It was 1997. The Spice Girls were blowing up the music charts, and I was depressed as a teenager could be (the two, unrelated).

Three years prior, at the age 13, I began my journey with alcohol, chugging tepid chardonnay I’d steal from my parents’ seemingly endless stash. I’d leave school on my skateboard and make my way home as fast as I could where I’d down a bottle, sometimes two, before anybody had the wherewithal to stop me.

And seven years before that, I scored my first goal in an AYSO soccer match, and proceeded to cry because all the cheering and attention was too overwhelming.

Nōn Wels

Writer, Podcaster, and Mental Health Advocate

Had I known of Aron’s seminal work, or even heard of the term, “highly sensitive person,” I wonder if that might've helped me avoid a whole lot of pain and anguish. The reality, at least in my experience, is that there’s not much wondering happening in survival. And at the time, I was in survival mode, even if I didn’t know it yet.

I was a sensitive little bean from day one, and not just in the emotional way. My mom would tell me that she would have to, quite frequently, hose me down in the backyard because my diaper refused to hold what my chronically upset tummy had to offer.

(There’s fascinating research2 that explores this relationship between highly sensitive people—or folks with sensory-processing sensitivity—and irritable bowel syndrome. I’ve had a sensitive stomach most of my life.)

I’ve always been emotionally sensitive, too, which never pairs well with a father whose rage and control seemed bountiful and unceasing, and a mother who tried to protect us and ultimately failed.

I lived in a house that was fueled by my father’s emotional peaks and valleys. In moments, he could be sweet and loving, and then a flip would switch so swiftly none of us would see it coming, like the time he threw a stray cat from our balcony like a football because he was angry that my younger brother and I, both six and nine years old respectively, brought the malnourished feline inside the house to care for it. My dad was allergic after all.

* * *

I never felt fully safe growing up, and as a result I learned to protect myself by shutting down. On any given day, this could look like me being quiet, or even shy—though I have a feeling the shyness was more like a symptom of my environment than anything else). It also could look like me being disengaged when my siblings were fighting or yelling.

That quiet detachment is the stuff that was on the surface. Underneath, I was writhing with shame, anxiety, guilt, fear, sadness, a tense stomach, a heaviness in my chest. All of which I tried to hide, and for a while I was pretty stellar at hiding. The after-school, one-person wine parties helped with that.

Drinking was something that I could control in an environment that often felt very out of control. It felt good. I felt relief. I felt, if only for a moment in time, some distance from the hyper-vigilance of living with such a soft, sensitive heart.

Yet, soon I’d learn that while my shutting down served as a form of protection, it also served as a form of destruction.

After my sister went off to college, I became my parents’ mediator. Not in any official way, of course, just in the way that naturally occurs when you have two very dysfunctional parents and one very emotionally dysregulated but deeply empathetic kid.

I have vivid memories of my mother crying on my shoulder, telling me about how awful my father was. Then, later that day, I’d listen to my dad scream about my mother. I was caught in between two broken creatures, and my heart couldn’t take the weight. So I learned to escape.

I escaped with the aforementioned booze, a brief bout of self-harm, and spending as much time away from home as I could with early bike rides to school and after-school skate sessions until my shins were scabbed over.

But my favorite way to escape was to read. I read voraciously, immersing myself in stories that were unlike my own. I’d take journeys to magical worlds with dragons and faeries. I’d yearn to be seated around a campfire with Jack London and his wolf-dog3. I imagined myself romping around the Ozarks with Old Dan, Little Ann, and young Billy Coleman4. Some of my fondest memories were the weekly trip to the library with my mom and my siblings. It was a little respite from home, surrounded by books, those little portals to empathy.

When high school rolled around, all of the love I had for reading was overshadowed by the crippling anxiety I might be called on for my perspective on, for instance, what Orwell had to say about the evils of totalitarianism. I was not only fearful of any criticism or feedback my teacher might give me, I was also terrified of what my peers would think of what the quiet little boy might say.

I lacked self-confidence, and it showed. I suspect it’s why I had a bully. The bullying mostly consisted of mean words and evil eyes, but on occasion he’d get in my face, try to intimidate me, and provoke me into a fight. Being highly sensitive, I did everything in my power to avoid him like the plague, but on the occasion he’d track me down, I’d muster up the will to ask him, “why are you doing this?” He never had an answer, which of course inspired me to retreat back into my own head to wonder what the hell I was doing wrong to be a target of a guy with a flattop.

After high school, around nineteen, I ran head first into an eating disorder. I basically stopped eating, more or less (mostly less), for about a decade until a Welsh doctor told me my heart would stop if I continued down the path I was heading. Even if I didn’t know it then, I wasn’t ready to let my heart die before I could open it for the first time.

Over the next ten years, slowly and steadily, I learned to let a little light in. It was all at once beautiful and painful, full of both loneliness and connection. I tried therapy, ghosted a therapist or two, then eventually found a therapist who I felt comfortable with. I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder, which was one of the most relieving and validating moments of my life. I found some medication that helped me avoid, for the most part, being a relentless Eeyore. I eventually quit drinking.

And, most of all, I discovered what safety means in the form of a human named Jessica. She saw me before I saw me: a highly sensitive person unanchored by any real sense of identity, purpose or meaning. Just a little sensitive bean adrift in a sea of repression. She saved my life, and I’m forever grateful.

As I look back on my childhood and the experiences I’ve had, I grieve what could have been, and at the same time I’m a middle-aged dude who used to think he’d never live past his teens. The truth is that I wouldn’t be here without the safety that people like Jessica provided me, and also I wouldn’t be here without the immeasurable privilege I lived with as a white cis-het guy who had the access and means to seek healthcare, therapy, and support.

I once thought being highly sensitive was a burden. I see it now as a superpower, one that requires curiosity, an open heart, clear boundaries, feedback, emotional awareness, an examination of assumptions and biases, and the safety to wield it.

There’s not a highly sensitive person diagnosis, and there doesn’t have to be. If you are reading this right now and you feel like it resonates with you, I’m grateful for you. The question now is, “what are you going to do with that great superpower of yours?”

References:

1. The Highly Sensitive Person by Elaine N. Aron, PhD

2. https://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-538-en.html

3. Where the Red Fern Grows by Wilson Rawls

4. Animal Farm by George Orwell

Talk Therapy as an Intervention for Highly Sensitive Person Traits

Talk therapy can be a highly useful modality to help highly sensitive individuals navigate the unique challenges associated with their personality trait. The goal of this intervention is to help a highly sensitive individual enhance their overall wellbeing and quality of life. Areas of focus may include:

- Validation and Understanding - Therapists can help HSPs understand that their sensitivity is a natural and valid part of their personality, not something to be ashamed of. This can foster self-acceptance and reduce feelings of isolation.

- Emotion Regulation – By developing strong emotion regulation skills, HSPs can learn to utilize healthy coping mechanisms to manage intense emotions and reduce emotional reactivity.

- Self-Exploration and Identity Work can help HSPs understand themselves better, build a strong sense of self, and embrace their "highly sensitive" identity, leading to greater self-acceptance and a more fulfilling life.

- Sensory Management - Therapists can offer practical tips for managing sensory overload, such as creating calming environments, utilizing noise-canceling headphones, or taking breaks in stimulating situations.

- Interpersonal Skills - Therapists can help HSPs develop effective communication skills to express their needs and set healthy boundaries with others, preventing emotional exhaustion and overstimulation.

Ultimately, the most effective interventions will depend on the individual HSP's specific needs and preferences.

Download our free patient handout, “5 Ways to Boost Your Powers as a Highly Sensitive Person”

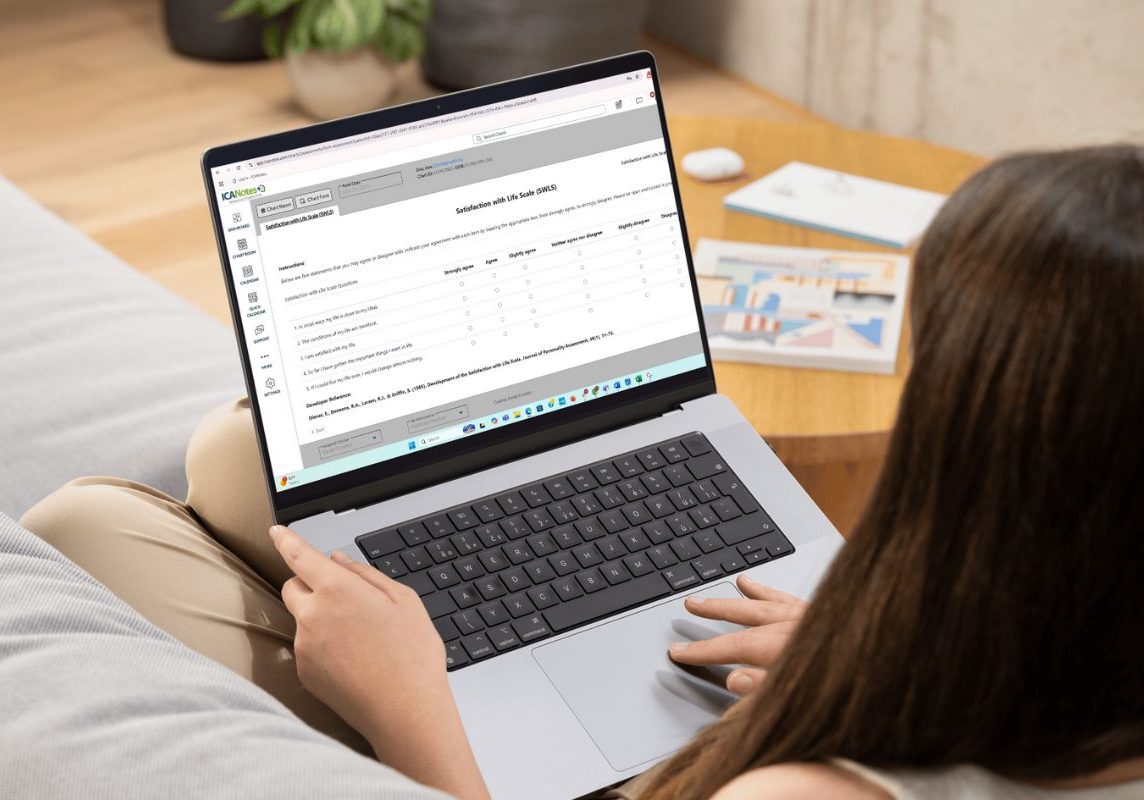

Document Client Progress with ICANotes

Tracking a client’s response to therapy is crucial for measuring progress toward their goals. ICANotes offers powerful documentation tools that allow you to create detailed and personalized progress notes quickly and efficiently after each session. This ensures you're prepared, organized, and ready to provide the best possible care at your next appointment.

ICANotes goes beyond progress notes, streamlining compliance practice management, and billing processes so you can spend more quality time with your clients. Schedule a demo today or start your free trial to experience how ICANotes empowers you to deliver the most effective and high-quality care possible.

About the Authors

Kaylee, a certified grief counselor and social worker, has dedicated the past decade to reshaping our understanding and support of grief. With experience at a nonprofit hospice, she's empowered individuals to navigate their grief journeys, recognizing that loss extends beyond death. As an author, speaker, and event organizer, Kaylee fosters spaces for acknowledging and embracing life's most challenging moments. Her work has been featured across various media, amplifying voices and broadening awareness of the diverse sources of grief in our lives.

Nōn Wels

Nōn Wels (he/him) is a writer, podcaster (You, Me, Empathy; We Can’t Do It Alone), mental health advocate (The Feely Human Collective), and best friend to dogs everywhere. In his work as a community builder and mental health advocate, Nōn has spoken publicly on topics such as Mental Health in Podcasting (Podcast Movement) and Growing In Connection with Others (The Mighty), and led feely workshops for Chapman University, the Laguna College of Art and Design, Project HEAL, and the Eating Recovery Center. Nowadays, you can find Nōn fostering dogs, consulting aspiring podcasters, running a little Studio Ghibli-themed Airbnb, and trying to remember to breathe. You can connect with Nōn at NonWels.com.

Recent Posts

Sources

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/highly-sensitive-person

- https://healyournervoussystem.com/6-facts-about-highly-sensitive-people-based-on-research/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886915301033?via%3Dihub

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/highly-sensitive-person#high-sensitivity

- https://hsperson.com/faq/evidence-for-does/

- https://hsperson.com/test/highly-sensitive-test/

- https://jpcp.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-538-en.html