Blog > Compliance > Legal & Liability Issues in Suicide Care for Clinicians

Suicide Risk: Documentation, Duty to Warn, and Foreseeability

Effective suicide risk care balances patient safety, confidentiality, and your legal duties. This guide explains how foreseeability is evaluated in malpractice, when duty to warn/protect applies, and which documentation practices best demonstrate sound clinical judgment.

Last Updated: August 21, 2025

What You'll Learn

- A clear, repeatable workflow for suicide risk care—screening (e.g., C-SSRS/ASQ), structured assessment (SAFE-T), concise risk formulation, and when to reassess.

- How foreseeability is judged in malpractice and how to show reasonable care through documented patterns of assessment → interventions → follow-up → consultation.

- The difference between duty to warn and duty to protect, including when disclosures are permitted/required under HIPAA’s serious & imminent threat standard and key 42 CFR Part 2 caveats.

- Exactly what to chart to reduce liability—tool/results, risk level with rationale, means-safety and Safety Plan details, time-specific follow-ups, consultations, and disclosure logs—and how ICANotes streamlines each step.

Contents

What “Suicide Risk” Means in Clinical Care

Suicide risk is the likelihood that a patient will engage in self-harm or suicide, based on current ideation, plan, intent, past behaviors, and the balance of risk and protective factors. In accredited settings, best-practice standards expect validated screening at entry points and, when positive, a structured risk assessment that informs your care plan and follow-up.

When suicide risk is identified, assessment must be paired with timely, structured intervention. Using a framework such as the six-step crisis intervention process helps clinicians move from evaluation to action by guiding safety decisions, escalation, and documentation in high-risk situations.

Definition of Suicide Risk

Suicide risk is the likelihood of self-harm or suicide based on current ideation, plan, intent, behaviors, and risk/protective factors. Clinicians must assess, document, and act accordingly.

Screening vs. Assessment (and Why It Matters Legally)

Accredited settings should screen with a validated tool and, when positive, complete a structured suicide risk assessment that addresses ideation, plan, intent, behaviors, and risk/protective factors. Cite the tool used (e.g., C-SSRS, SAFE-T), your risk formulation, and the interventions/follow-ups chosen.

- Screening: a brief, validated set of questions to flag risk (e.g., the C-SSRS). Positive screens trigger a fuller evaluation.

- Structured assessment: a deeper, repeatable workflow such as SAFE-T that documents (1) risk factors, (2) protective factors, (3) suicide inquiry (ideation, plan, intent, behaviors, means), (4) risk level with matched interventions, and (5) documentation of your formulation and follow-up.

This structure supports clinical care and shows you acted reasonably if your decisions are later scrutinized.

What to Evaluate Every Time

-

Ideation & intent: frequency, intensity, controllability; explicit intent to die.

-

Plan & means: specificity, lethality, access to means; steps taken toward an attempt.

-

Past behavior: prior attempts, rehearsals, or self-injury.

-

Risk factors (often more static): prior attempts, psychiatric comorbidity, substance use, agitation, recent loss, access to lethal means.

- Protective factors (often more dynamic): reasons for living, social supports, treatment engagement, cultural/spiritual buffers.

Documenting these elements, plus your risk level and intervention choices, aligns with SAFE-T and Joint Commission guidance.

Risk Formulation > Risk Labels

Rather than relying only on “low/moderate/high,” write a brief risk formulation that connects the data to your decisions (e.g., “Acute risk elevated today due to new intent + access to firearm; mitigated by partner supervision; initiated means-restriction counseling and next-day follow-up”). A clear formulation, repeated over time, is central to demonstrating sound judgment.

Reassessment Triggers

Risk is dynamic. Reassess (and update the note) when: symptoms shift, stressors emerge (breakup, job loss), medications change, after ED visits/discharge, or when collateral information raises concern. Joint Commission resources emphasize policies for reassessment and monitoring for patients at risk.

How This Connects to Liability

In malpractice cases, the question is not whether suicide was “predictable,” but whether harm was reasonably foreseeable given what you knew (or should have known) and whether you took reasonable, documented steps (assessment, safety planning, follow-up, consultation). A consistent, tool-anchored workflow strengthens that record.

Suicide Risk Documentation Essentials (defensible charting)

-

Tool used & results (e.g., C-SSRS items endorsed), risk formulation, and specific interventions (safety plan elements, means-restriction counseling, crisis resources).

-

Follow-up: exact timing and modality; who is responsible.

-

Collaboration: supervision/consultation, care coordination, and any disclosures made under HIPAA’s serious and imminent threat allowance—include your good-faith rationale and the minimum necessary information shared.

Screening & Assessment Tip

Keep a reusable checklist (screen → assess → formulate → act → document → follow-up) to standardize care across clinicians and visits.

Foreseeability in Malpractice: What Courts Actually Look For

Foreseeability isn’t about predicting the future; it’s about whether a clinician knew or reasonably should have known there was a meaningful suicide risk, and whether reasonable steps were taken in response. In malpractice cases, plaintiffs must still prove the classic elements (duty, breach, causation, damages), but the dispute often centers on whether suicide was reasonably foreseeable given the information available and the care provided.

How Foreseeability is Evaluated

Courts and experts typically examine whether you:

-

Identified and evaluated suicide risk (history of attempts, current ideation/intent, plan/means, risk and protective factors).

-

Formulated and implemented a treatment/safety plan that matched the observed risk (e.g., means-restriction counseling, higher level of care, closer follow-up).

-

Monitored and adjusted the plan as the clinical picture changed (e.g., after ED discharge, new stressors, med changes).

-

Documented your reasoning—not just what you did, but why you did it (or chose not to).

When these elements are visible in the record, they demonstrate reasonable professional judgment rather than negligence.

“Pattern Over Time,” Not a One-and-Done Note

Foreseeability is assessed across the course of care, not just at intake. Serial assessments, explicit risk formulations, and timely modifications (tightened follow-up, additional supports, consultation) show you were actively managing dynamic risk rather than assuming it was static. Consistent documentation of this pattern is repeatedly cited as protective.

Practical Guardrails That Support Foreseeability

-

Use a structured approach (e.g., SAFE-T) to anchor what you assess and how you match interventions to risk; standardization reduces omissions and clarifies clinical judgment.

-

Consult and coordinate. Document curbside or formal consultation, team communication, and collateral contacts when appropriate—these show diligence when risk rises.

-

Avoid “no-harm contracts” as a substitute for assessment and planning; they can be one piece of a broader plan, but they do not demonstrate adequate evaluation or risk mitigation by themselves.

Documentation That Makes (or Breaks) the Case

Brief, contemporaneous notes that another clinician could follow are best. For elevated or fluctuating risk, make sure your chart clearly shows:

-

Risk formulation (why risk is low/moderate/high today).

-

Specific actions tied to risk (means counseling, safety planning details, level-of-care decisions, contacts notified).

-

Follow-up cadence (how soon, by whom, and why).

-

Decision rationale (why you chose X over Y, including when you considered but declined hospitalization).

-

Reassessment triggers and results (ED visit, new firearm access, major loss, med change).

Well-reasoned documentation is both good care and a strong defense because it evidences reasonable care at the time decisions were made.

A Legally Informed Framing You Can Adopt

Scholars in forensic psychiatry describe “probable standards” that map legal reasonable care onto clinical tasks (e.g., thorough inquiry, risk formulation tied to interventions, ongoing monitoring, and clear documentation). You don’t need to predict suicide; you need to show a systematic, defensible process for recognizing and responding to suicide risk as it evolves.

Bottom line: Foreseeability hinges on your process, not clairvoyance. A structured assessment, matched interventions, timely adjustments, and transparent documentation demonstrate that you exercised sound clinical judgment, which is what courts expect.

Free Download:

Suicide Risk Assessment Guide

Turn tough conversations into a clear, defensible workflow. Get scripts, checklists, and templates that help you assess, document, and plan for safety in one visit.

What you’ll get

-

Conversation prompts (what to ask—and what to avoid)

-

A ready-to-use Suicidal Ideation Checklist to spot red flags fast

-

Plug-and-play Safety Plan and Treatment Plan templates

Duty to Warn vs. Duty to Protect

“Duty to warn” is often framed today as a broader duty to protect. Depending on your state, you may be required or permitted (with immunity) to take steps that reduce a serious and imminent risk of violence to an identifiable person. Those steps can include warning a potential victim, notifying law enforcement, arranging hospitalization or a higher level of care, and tightening supervision and follow-up—choose what reasonably reduces risk in the circumstance and document your rationale.

How State Laws Differ

States generally follow one of three approaches: mandatory duty, permissive duty, or no specific statutory duty (often with immunity if you act in good faith). Know your state’s statute and case law and align your policies accordingly.

When the Duty is Triggered

The classic U.S. case, Tarasoff, established that clinicians may owe a duty to take reasonable care when a patient poses a serious threat to an identifiable third party. The exact trigger and required actions vary by state, but the core idea is that once you know or should know of a credible, specific threat, you must take reasonable protective steps.

What About Threats of Self-Harm (Suicidality)?

Many duty-to-protect statutes focus on threats to others. For self-directed violence, your authority to involve family or authorities typically comes from HIPAA’s “serious and imminent threat” provision and your general standard of care (e.g., arranging hospitalization). Under HIPAA, you may disclose PHI, in good faith, to people able to lessen the threat (including family or police), sharing the minimum necessary. State law still governs what is required vs. permitted.

Confidentiality Overlays You Must Respect

-

HIPAA (45 C.F.R. § 164.512(j)): Permits disclosures to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat, consistent with law and ethical standards, to someone who can reduce the risk (including the intended victim). Not a mandate, but some states do mandate action.

-

42 C.F.R. Part 2 (SUD records): Much stricter. Without consent, disclosures are allowed only in narrow circumstances (e.g., a bona fide medical emergency), with specific documentation requirements. Build your protocols so staff recognize when Part 2 applies.

Practical Steps That Satisfy (and Document) the Duty

-

Assess & decide: Describe the specific threat, target, and why it meets your state’s threshold for action.

-

Choose reasonable protective measures: Examples include warning the identifiable person, calling law enforcement, arranging ED evaluation/hospitalization, removing or restricting access to means, increasing observation, and accelerating follow-up. Match the action to the risk.

-

Limit what you share: Disclose only the minimum necessary to those who can reduce the threat; if Part 2 applies, follow its emergency-disclosure rules.

-

Record the who/what/when/why: Exactly whom you warned or notified, what you shared, when you did it, and your good-faith rationale (including any consultations). This documentation is central to showing you met the duty.

How to Explain it to Teams (Clinician Script)

“Our duty is to protect, not only to warn. If there’s a serious and imminent threat to a specific person, we take reasonable steps to reduce risk—warning the person at risk, notifying police, arranging higher care, and tightening follow-up—while sharing the minimum necessary information and documenting our good-faith judgment.”

Bottom line: Treat “duty to warn” as one tool within the wider duty to protect. Use a clear decision pathway, consult when in doubt, act to reduce risk, and chart your reasoning—this aligns clinical care with legal expectations

Screening & Structured Assessment for Suicide Risk

Why this matters: High-reliability suicide care starts with validated screening at intake and other key touchpoints, followed by a structured risk assessment when screening is positive. Accrediting bodies (e.g., The Joint Commission’s NPSG.15.01.01) expect organizations to standardize these steps.

Step 1: Screen with a Validated Tool

Use a brief, validated screener appropriate to your setting and population, then document the tool and result in the note.

-

C-SSRS Screen: widely used across settings to identify current and recent suicidal ideation/behavior.

-

ASQ (Ask Suicide-Screening Questions): a four-item, ~20-second screen; validated in youth and studied in adults; free toolkit available.

Positive screen → proceed to structured assessment (below). Negative screen with concerning context (e.g., recent attempt, ED discharge) still warrants clinical judgment and safety education.

Step 2: Conduct a Structured Suicide Risk Assessment

Adopt a repeatable framework so your assessment, interventions, and follow-up are transparent to any covering clinician.

-

SAFE-T (SAMHSA) organizes assessment into five parts:

1) Risk factors, 2) Protective factors, 3) Suicide inquiry (ideation, plan, intent, behaviors, access to means), 4) Risk level + matched interventions, 5) Documented plan & follow-up.

-

Document a brief risk formulation that connects the data to your decisions (e.g., why risk is low/moderate/high today and what you’re doing about it). This supports clinical care and legal defensibility.

When to (Re)assess

Risk is dynamic. Beyond first contact, reassess and update the plan:

-

with any increase in ideation or suicidal behavior,

-

at pertinent clinical changes (new stressor, major loss, med change, access to lethal means),

-

before treatment changes, and

-

at inpatient discharge / post-ED transitions.

Tie Assessment to Action (and document both)

Your note should make it obvious how findings drove care decisions:

-

Means-safety counseling (e.g., firearm/medication access) and who will help implement.

-

Safety Planning Intervention (Stanley-Brown): create or revise a written plan (warning signs, internal coping, social/professional supports, emergency steps). Provide a copy to the patient and record how you reviewed it.

-

Level of care / follow-up: specific timing (e.g., “phone check tomorrow; visit in 48–72 hrs”), referrals, warm handoffs.

-

Consultation/collateral as indicated, with minimal-necessary details.

Minimum Elements to Capture in the EHR (copy/paste checklist)

-

Tool used & score/result (C-SSRS/ASQ).

-

Risk/protective factors + suicide inquiry details (ideation, plan, intent, behavior, means).

-

Risk formulation (why risk is low/moderate/high today).

-

Interventions chosen (means-safety steps, Safety Plan created/updated).

-

Follow-up cadence & handoffs (who, when, how).

-

Consultation/collateral/disclosures and your good-faith rationale.

-

Reassessment trigger (why you re-evaluated today).

Bottom line: Screen with a validated tool, assess with a structured framework, and make the documentation show your clinical reasoning → interventions → follow-up. This improves care quality and demonstrates a defensible, standards-aligned process.

Documentation That Reduces Liability

Good notes don’t just record care—they prove you recognized suicide risk, exercised sound judgment, and took reasonable actions. Accrediting and federal guidance emphasize documenting risk level with rationale, interventions matched to risk (including means-safety and safety planning), and specific follow-up plans. Standardizing these elements strengthens care and your legal position. For broader principles of defensible documentation, see our Clinical Documentation/Utilization Review guide.

What Every High-Risk Note Should Include

-

Tool used & results: name the validated screener/assessment (e.g., C-SSRS, SAFE-T) and the exact responses or score that triggered action.

-

Risk formulation (today): state low/moderate/high and why (ideation, intent, plan, access to means, recent behaviors, risk/protective factors). Tie the formulation to the plan you chose.

-

Interventions matched to risk: e.g., means-restriction counseling, Stanley-Brown Safety Plan created/updated (and patient received a copy), medication or psychotherapy adjustments, contact with supportive others, or higher level of care.

-

Follow-up cadence: the exact interval (e.g., “call in 24 hours; visit in 48–72 hours”), who is responsible, and what will trigger earlier contact.

-

Consultation & coordination: names/titles, date/time, and advice received (supervisor, psychiatrist, PCP, ED). If you disclose information to reduce an imminent threat, record who/what/when/why and that you shared the minimum necessary under HIPAA’s threat exception.

-

Disposition & transitions: rationale for outpatient vs. ED/hospitalization, any warm handoffs, and instructions/resources given (hotline, crisis text, local mobile crisis).

Phrases That Make Your Reasoning Clear (copy/paste)

-

“Risk formulation: Acute risk moderate today due to [new intent + access to firearm]; protective factors include [partner supervision].”

-

“Means safety: Reviewed firearm/med storage; partner agrees to remove firearm to off-site storage by tonight; verified plan.”

-

“Safety plan: Completed Stanley-Brown; patient received copy; practiced Steps 1–3 in session.”

-

“Follow-up: RN phone check tomorrow; therapy visit 72 hours; earlier contact if ideation intensifies or access to means recurs.”

-

“Consultation/disclosure: Discussed case with on-call psychiatrist (1900 hrs). Disclosed minimal PHI to [name/role] under HIPAA 164.512(j) due to serious and imminent threat; content limited to risk and safety actions.”

Common documentation gaps (and how to close them)

- Assessment without rationale → Add a one-sentence why behind the risk level and the action you chose.

- Safety plan mentioned, not specified → Record which steps were covered and that the patient received a copy.

- No evidence of follow-up → Put dates/times and modality in the note (call, portal message, visit) and close the loop at the next contact.

- No lethal-means counseling → Document the discussion, concrete storage/removal steps, and who will help implement them.

- Sparse records after critical changes (ED discharge, new firearm access, med change) → Add a reassessment entry with updated formulation and revised plan.

Risk-management bottom line: Clear notes that show assessment → rationale → intervention → follow-up are protective. Insurers specifically advise documenting your thought process alongside findings and plans.

EHR Tip

Build an EHR template that mirrors SAFE-T’s five steps (risk/protective factors, suicide inquiry, risk level + matched interventions, and documentation checklist). It reduces omissions and supports a consistent standard of care.

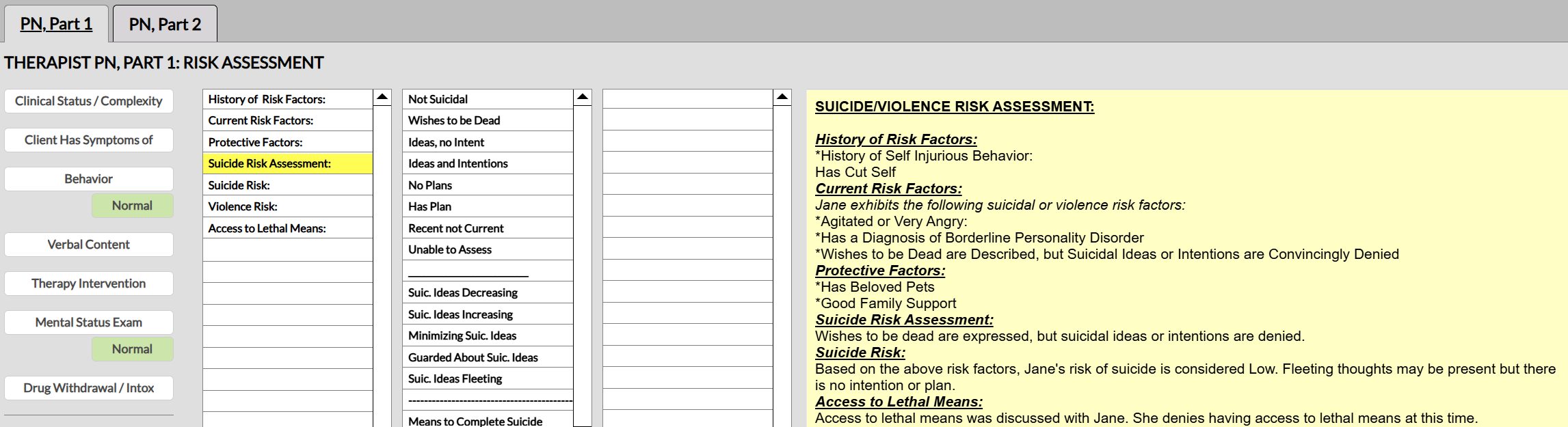

In the ICANotes EHR, every clinical note features a comprehensive menu-driven suicide risk assessment template. This helps ensure compliance with suicide risk assessment policies and documentation requirements.

Confidentiality & Disclosures

Your default is confidentiality. But when suicide risk escalates, HIPAA and related rules outline when you may (or must, under state law) disclose limited information to reduce danger.

The HIPAA baseline

-

Serious & imminent threat (good-faith standard). You may disclose PHI if, in good faith, you believe it’s necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to a person or the public, and you share it only with someone reasonably able to lessen the threat (e.g., family, law enforcement, the potential victim). Use the minimum necessary information and document your reasoning.

-

Family & friends involved in care. With the patient’s agreement (or when the patient has the opportunity to agree/ object, or is incapacitated and disclosure is in the patient’s best interests), you may share information directly relevant to their involvement in care or payment. This is distinct from the “serious and imminent threat” pathway and often useful for routine support and safety planning.

When Disclosure is Required (state law)

Many states impose duty-to-warn/ protect obligations when there’s a credible, specific threat to an identifiable person. Some states make this duty mandatory; others permissive with immunity. Know your state’s rule; if it requires action, follow it and document the steps you took.

Special Confidentiality Overlays

-

Substance Use Disorder records (42 CFR Part 2). These records carry stricter protections than HIPAA. Without consent, disclosures are limited (e.g., bona fide medical emergency, specific court order). If you disclose due to a medical emergency, you must document in the record: recipient’s name/affiliation, discloser’s name, date/time, and the nature of the emergency. (Note: HHS finalized updates aligning Part 2 more closely with HIPAA; review your policies.)

-

Psychotherapy notes (HIPAA-defined). These are the therapist’s separate process notes and receive extra protection: in general, they require a specific authorization for disclosure (with narrow exceptions, e.g., use by the originator, training, or to defend a legal action). Keep them separate from the medical record.

-

Minors & personal representatives. Parents are usually the minor’s personal representative, but access and disclosure depend on state law and exceptions (e.g., when the minor legally consents to care or there’s a risk of harm from parental access). Confirm your state’s rules before releasing information.

What To Document When You Disclose

-

Risk & rationale: What you believed the serious and imminent threat was and why disclosure would reduce it (HIPAA 164.512(j)).

-

Recipient & scope: Who you told and exactly what you shared (minimum necessary).

-

Timing & method: When/how you made contact; any effort to reach the patient first if appropriate.

-

Follow-through: Actions taken (e.g., advising removal of lethal means, arranging ED evaluation) and planned follow-up.

-

If Part 2 applied: Add the required emergency-disclosure details listed above.

Quick Decision Pathway (copy/paste into policy)

-

Is there a serious, imminent threat? → If yes, disclose minimum necessary to those who can lessen the threat; record your good-faith rationale.

-

Does state law mandate warn/protect? → If yes, take the required steps (warn potential victim, notify law enforcement, arrange higher level of care) and document.

-

Is any information Part 2-protected? → If yes, apply Part 2 rules; in emergencies, disclose to medical personnel and document per §2.51(c).

-

Could routine involvement of family/friends help? → Share care-relevant information under 164.510(b) with patient agreement or best-interests standard.

Bottom line: Confidentiality remains the rule. When suicide risk rises, HIPAA allows good-faith, limited disclosures to reduce imminent danger, state law may require action, Part 2 can further restrict SUD information, and psychotherapy notes are specially protected. Clear, minimal, well-documented disclosures align care with legal standards.

Frequently Asked Questions

How ICANotes Supports Suicide Risk Workflows

ICANotes helps clinicians turn best-practice suicide care into a repeatable, well-documented workflow—from validated screening to structured assessment, safety planning, and follow-up—so your chart clearly shows reasonable care and clinical judgment (key to meeting the standard of foreseeability in suicide risk cases).

1) Standardized screening → structured assessment

- Built-in, customizable templates let you embed validated screeners (e.g., C-SSRS/ASQ) and route positive screens to a SAFE-T–style assessment with required fields for ideation, intent, plan, behaviors, access to means, and risk/protective factors.

- Required fields & prompts reduce omissions: clinicians can’t close the note until risk level and rationale are documented.

2) Defensible Risk Formulation (today)

- Templates include a concise Risk Formulation box that ties findings to interventions (e.g., “moderate acute risk due to X; mitigated by Y; doing Z”).

- Smart text/phrases make it fast to capture exact patient statements, clinical reasoning, and the plan—without copy-paste drift.

3) Safety Planning and Means-Safety, Right in the Note

- One click to add a Stanley-Brown Safety Plan section (warning signs, internal coping, social/professional supports, crisis steps).

- Means-restriction counseling fields (firearms/meds/other methods) prompt you to record who will secure or remove means and by when.

4) Follow-up You Can See (and Track)

- Time-stamped follow-up plan (e.g., “phone check tomorrow; visit in 48–72 hours”) with assigned owner.

- Tasks & reminders populate your team’s to-do list so next-day checks and post-ED transitions don’t fall through the cracks.

- Use saved worklists/filters to review all active patients with recent positive screens or upcoming safety-plan checks.

5) Duty to Warn/Protect & HIPAA-Aligned Disclosures

- A dedicated Disclosure/Duty to Protect note segment captures the who/what/when/why, the minimum necessary information shared, and your good-faith rationale—supporting compliance when duty to warn/protect applies.

- Optional quick-pick reasons (e.g., serious and imminent threat, identifiable person at risk) standardize language and reduce free-text errors.

6) Care Coordination and Warm Handoffs

- Document consultations (supervisor, psychiatrist, PCP), attach referrals, and send internal messages from the chart.

- Transitions of care (ED/hospitalization) can be recorded with discharge instructions and scheduled outreach.

7) Privacy Controls that Match the Moment

- Role-based access and note-type separation support extra-sensitive content.

- Optional restricted sections and attestation prompts help teams share only what’s needed while preserving confidentiality standards

8) Quality Improvement and Audit Readiness

- Quickly pull a chart list of patients with positive screens, updated safety plans, or missed follow-ups.

- Audit trails show who documented what and when—useful for internal reviews and policy tuning.

Quick Start (copy/paste into your implementation checklist)

-

- Turn on your suicide screening template at intake and key touchpoints.

- Add a SAFE-T–style assessment with required fields for risk/protective factors, suicide inquiry, risk level + rationale, and interventions.

- Insert Safety Plan and Means-Safety sections; make “patient received copy” a checkbox.

- Build a Disclosure/Duty to Protect snippet that logs minimum necessary info and your good-faith reasoning.

- Create follow-up tasks (next-day call, 48–72-hour visit) and a worklist for active high-risk patients.

- Train staff on the screen → assess → formulate → act → document → follow-up pathway so every note tells the same clear story.

Bottom line: With ICANotes, every single step, from recognizing suicide risk to following up, is clearly documented, clinically sound, and legally defensible. That’s how you protect patients and your practice. Find out how ICANotes can help streamline your suicide risk assessment workflows by booking a demo with one of our product experts, or start a 30 day free trial (no credit card required).

Start Your 30-Day Free Trial

Experience the most intuitive, clinically robust EHR designed for behavioral health professionals, built to streamline documentation, improve compliance, and enhance patient care.

- Complete Notes in Minutes - Purpose-built for behavioral health charting

- Always Audit-Ready – Structured documentation that meets payer requirements

- Keep Your Schedule Full – Automated reminders reduce costly no-shows

- Engage Clients Seamlessly – Secure portal for forms, messages, and payments

- HIPAA-Compliant Telehealth built into your workflow

Complete Notes in Minutes – Purpose-built for behavioral health charting

Always Audit-Ready – Structured documentation that meets payer requirements

Keep Your Schedule Full – Automated reminders reduce costly no-shows

Engage Clients Seamlessly – Secure portal for forms, messages, and payments

HIPAA-Compliant Telehealth built into your workflow

Related Posts

Dr. October Boyles is a behavioral health expert and clinical leader with extensive expertise in nursing, compliance, and healthcare operations. With a Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) and advanced degrees in nursing, she specializes in evidence-based practices, EHR optimization, and improving outcomes in behavioral health settings. Dr. Boyles is passionate about empowering clinicians with the tools and strategies needed to deliver high-quality, patient-centered care.